Tate Britain's new retrospective of Lowry has sparked fresh debate, or should I say opened old wounds, drawn in the argument over the intentions and mental health of the divisive Mancunian.

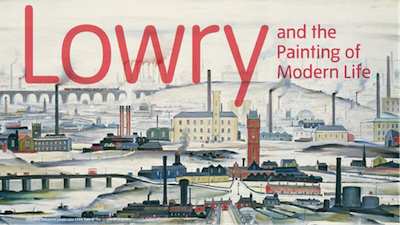

Lowry and the Painting of Modern Life exhibits landscapes of the industrial north. He painted them after work, from memory and imagination, and from a vantage point of not exactly a birds-eye view, but a second-storey window perhaps or the roof of a tall building. He used lines instead of brushwork, filling in chimney pots sooty black and brick walls red, the floor and sky are left white, and floating in the white skies are dark satanic mills, hospitals and factories. His pallet is bleak, it is as he said:

"I am a simple man, and I use simple materials: ivory black, vermilion, Prussian blue, yellow ochre, flake white and no medium. That's all I've ever used in my paintings."

They are laid out like scale models of imagined towns, his matchstick men are there to show how it all works, as toy cars at a traffic junction's plan.

The so-called matchstick men are assemblies of winter clothes walking hunched through the cold with bob hatted duffle costs in triangle skirts, and their matchstick cats and dogs. They walk the same white streets from painting to painting, dated from the 1920s into the 1970s, as Lowry and his industrial scene, one never tiring of the others company. They congregate in crowds, and it is through their interaction with one another that they come to life: Some appear lonely while others walk in stride and couples go hand in hand. In one piece a pair of old ladies scald some young guttersnipe who is frozen stiff and as a family passes the baby in the pram looks over at the noise. Lowry is people watching, and so his works are studies in human behaviour, as is apparent in his famous quote:

"Where there's a quarrel there's always a crowd... it's a great draw. A quarrel or a body."

There is no rose and blue period as in an exhibition of his contemporary Picasso, Lowry painted the same feelings on every canvas: Down two up, two down council house rows, through broken fences and Blitz rubble, past protest marches, blue faced mourners of pit tragedies, funeral processions, and crowds around the fever van, to foreboding churches on desolate hilltops. Of poverty and gloom, are Lowry's, and he really seems to wallow in it, but could it be he was wallowed in it? For in his work as a rent collector this was the life he came to know, it was a sad life, and as curators, T.J. Clark and Anne M. Wagner, note: 'he was a painter of modern life'.

The notes go on to say that, in this way, Lowry was like an impressionist. They say he was taught in evening classes at Manchester school of art by Frenchman, Adolphe Valette who 'preached the gospel of impressionism'. And that Lowry showed, as Charles Baudelaire put it in his essay The Salon of 1845, 'how great and poetic we are in our neckties and patent-leather boots.'

Although others have argued Lowry liked the 1920s, so that's what he painted, and so he was not a painter of modern life but a painter of the industrialisation and economic slump of the 1920s. Many believe this repetition evidence of autism, a claim many also deny, but which has led some to think of his as outsider art.

This also fails to explain a work like Cripples, depicting caricature dwarfs, humpbacks, and big headed women, painted at street level. He has put them close up caged in park gates as a freak-show behind the glass. Critics argue this was not modern life; Lowry did not paint a scene of cripples he saw but every cripple he had ever seen. The caption below the painting tells the story of a critic who made such a criticisms of Lowry and the painter took him on a trip to the outskirts and showed him these outcasts and that this was modern life.

However it is difficult to shake the feeling Lowry was looking down on them, which is an argument one could evidence, be it to a lesser extent, with just about every painting in this exhibit. They are all painted from above so Lowry is literally looking down, this also allows Lowry to show you the flow of the crowd, they enter the mill just like they enter the turnstiles of the football match. Like iron filings, they appear governed by forces greater than themselves. In the accompanying book there is a quote from John Berger who described them as: 'fellow-travellers through a life which is impervious to most of their choices'.

The book continues, "This verdict, rings true: life within a community responsive to personal choice would be a world without the strictures of class. It was not the world that Lowry knew." This final line refers to Lowry being of middle-class, a conservative, who toured the industrial communities in his work as a rent collector, hammering on the door. These facts have led many to conclude Lowry was indeed looking down on the working class and without empathy.

However no such accusations were ever made of Van Gogh who was similarly from a family of middling means, and painted similar people though working in a field as opposed to a mill or a mine. The difference being Van Gogh's peasantry are deigned deified, or painted as the kings hanging in the British portrait gallery, or 'soothed beneath the artists loving hand.' I think one could make the same case for Lowry.

Lowry and the Painting of Modern Life is showing at Tate Britain until 20 October.

Review by Harrison Drury