This show has torn up my view of the Pre-Ralphaelites. Instead of being bored by the neurotic detail of these paintings I’m now wooed by it as if these works were weird ‘retina-display’ visions; and instead of finding the languid women cheesy there’s a feeling of people trying to ignite a sense of romanticism in an over industrialised society.

I guess I’d always held what seemed to be a popular belief about the Pre-Raphaelites that they were too fussy and a bit of an anachronism, but perhaps I’d never really seen behind this facade - and it’s a testament to how well the show is put together that it can blow away these misconceptions.

I didn’t actually know that the Pre-Raphaleities were formed in 1848 at essentially a time when ruptures in the industrialized society were showing and many felt that in the machine age beauty and spirituality had been lost - you could substitute 2012 for 1848 easily.

Obviously, as I now properly realise, the term Pre-Rapaelite is about the desire to hark back to an earlier style of painting, essentially the detailed compositions of Quattrocentro Italian and Flemish art. What’s neat about the show is that in the first room you can see Lorenzo Monaco’s, Adoring Saints Altar Piece from 1407 alongside Millais’ Isabella from 1848 - the later piece is directly inspired by the former, with the two figures in the centre of the altar piece appropriated and re-envisioned as the two lovers on the right of Millais’ painting. It’s brilliant to see where the Pre-Rephaelite inspiration came from which is helped by the fact this is the first time Lorenzo Monaco’s Altar Piece has left the National Gallery since 1848.

From the first room on I was then ready to drop my pre-conceived Pre-Raphaelite views and really engage with the show - incidentally there’s also a great drawing in the first room by Millais which shows just what a great draughtsman he was.

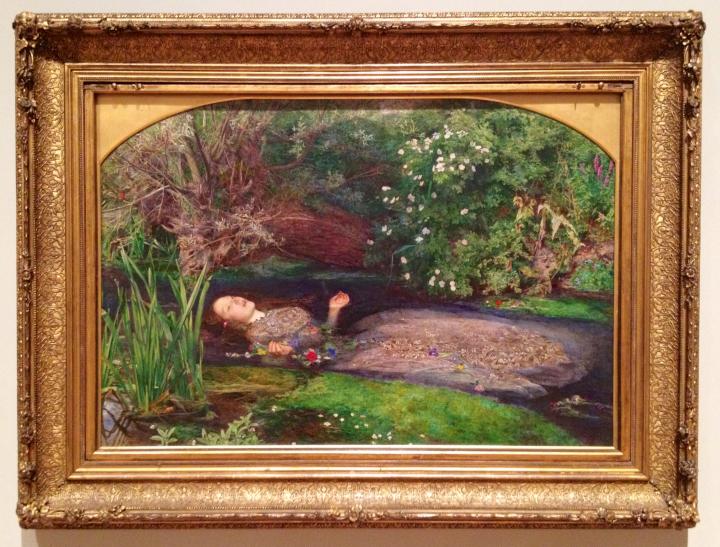

The fresh feeling for the paintings made me enjoy works like Millas’ Ophelia and Ford Maddox Brown’s The Pretty Baa Lambs much more. The insane details of the paintings that had previously left me cold now transported me into some kind of meditative state of a hallucinatory vision. You don’t really see everything at once like that in a heightened state of awareness where a leaf is seen in the same details as Ophelia’s hand and there’s something radical about that overall intensity of vision. (Weirdly it actually reminds me of Hockney’s photo montages where in the same way each thing in the montage is made of a separate photo so everything is on focus.)

According to the curators this detail of painting was a key part of the works and Millais would even say that he only painted the size of a shilling each day. Intriguingly Ophelia was actually painted in Kingston, and much of it was painted in the open air, with Millais traveling to Kingston on the then new train network, so even though the artists criticised the industrial society they were fully urbanised.

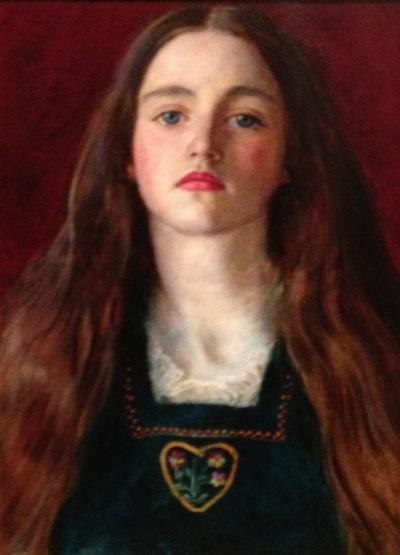

The next painting that really got me was Millais’ portrait of Sophie Gray - she looks out in such a modern confident way that the picture seems tight and contemporary. Alongside it are two fascinating photographs by Julia Margaret Cameron where instead the artist is trying to use photography in painterly fashion to sum up a dreamy blurry atmosphere - a far cry from out current obsession with pixel density and clarity.

The last room then has the most extraordinary painting by William Holman Hunt based on Tennyson’s poem The Lady of Shallott, about a woman destined suffering from a mysterious curse where she must weave pictures on a loom and can only see the world through a mirror - the painting captures the moment where she decides to break the curse and to turn around and look out of the window directly instead of at it’s reflection in order to see Sir Lancelot, but by turning she seals her fast.

It is a genuinely bizarre painting and the first time it has been to Europe for year - it seems as if the Lady of Shallott’s hair is all on fire, her arms are twisted back on themselves and all over the painting are stands and wriggling lines of colour that depict the yarn she is threading. There is something abstract about the painting with the vibrant colours and looping line that remind me of looping pencil lines in Ben Nicholson’s paintings.

This is an extraordinary show that blows away the old views of the Pre-Raphaelities - it’s title sets the scene with a purposeful juxtaposition of the word Victorian and the phrase Avant Garde - and the exhibition is a success in working on this juxtaposition and getting you to see all these paintings in a new, fresh light.

Review by Robert Dunt