This exhibition is heavily authored. The explicit intent is to re-locate Munch – popularly (and literally, with The Scream) the posterboy of fin-de-siecle symbolism – as a twentieth century artist, less post-Impressionist as pre-Expressionist. It is an intent with little relevance outside the academic discourse of art history. For the casual exhibition goer - whose interests range freely across the aesthetic, the thematic, the psychological, the spectacle -there can be no real interest in an act of canonical (re)categorising of an artist. The pleasure of this exhibition lies then in where this reinterpretative curation illuminates Munch’s practice and objectives. For example, annotating his sequence of paintings entitled The Fight (1916, 1916, 1932, 1932-35) with contemporary films using the same visual convention of black and white paired antagonists certainly invigorates a reading of the work – who cares what it says of Munch’s status as a cinephilic proto-modernist?

Edvard Munch

New Snow in the Avenue 1906

Munch Museum

© Munch Museum/Munch-EllingsendGroup/DACS 2012

Repeatedly, too much is made of too little evidence. Least interesting are the photographic self-portraits from the 1930s, frequently three-quarter profile shots. The speculation that these are experiments in testing the limits, and complementary strengths, of photographic and painted portraiture may well be biographically accurate, but they are only of interest when placed in meaningful dialogue with portraiture intended for public consumption. It is only possible to see the bluntest of contrasts between these renderings of the face – all angle and line - and the ghoulish, daubed masks in The Death of the Bohemian (1925-26). If Munch’s aim was to prove painting’s expressive superiority to photography, it’s an uneven contest, with the fledgling art form set up to fail. More plausibly, these photographic self-portraits – along with the double-exposure shots of various artworks and locations in Oslo – are experiments with new technology. In content, attitude and appearance, they probably differ but slightly from those first exploratory snaps many might make upon taking possession of a new iPhone.

Warned against this over-writing, there is much to enjoy here. The obsessive ruminations on the Weeping Woman - comprising five oil on canvas paintings, two lithographs, a charcoal on paper drawing, a sculpture and a photograph of the sculpture – will drive any viewer into a projective attempt at supplying the pieces, and the figure within, with psychological moorings and narrative context. Presented within the same room, the works force identification through irresistible insistence.

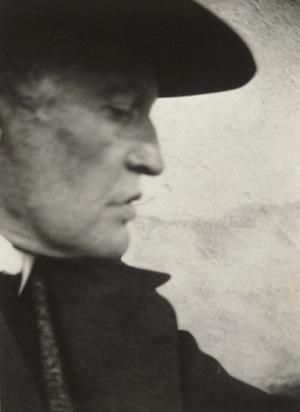

Edvard Munch

Self-Portrait with Hat (Right Profile) at Ekely 1931

© Munch Museum

Although repetition is the word used in the exhibition notes, the sensation is of revisiting, most potently in the second room which literally faces off a series of Munch’s late nineteenth century works with reworkings from three or four decades later. Munch’s return to these scenes – often of a staged trauma – compels the viewer also to return, and in doing so remember. Or rather, dismember. It’s easy to be cynical about Munch’s continual reproducing (for sale) of The Sick Child, his account of his younger sister Sophie’s painful childhood death. It’s harder not to see, and in seeing feel, the acceptance of life’s mundane horrors in the ever-softening brushwork of each reiteration, the desperate scratched rendering of 1885-86 – the freshly bereaved’s futile clawing instinct – slowing and thickening by 1925 into something that speaks of distance if not reconciliation, of the decades’ memorialising nostalgia if not precisely closure or acceptance.

Edvard Munch

The Sick Child 1907

Tate

© Munch Museum/Munch-EllingsendGroup/DACS 2012

Munch’s taste for the melodrama of the soul is apparent in Red Virginia Creeper (1898-1900), Galloping Horse (1910-1912) and Workers on Their Way Home (1913-1914), where foregrounded faces of emotional fixation converse with backdrops that are typically and impossibly both expansive and claustrophobic in their angularity. For all the apparent, brute external space, the impression is of internal states. These are attitudes towards a world, rather than worlds themselves. The countervailing forces of fluidity and stasis, create a dynamic inertia that is by turns deathly – On the Operating Table (1902-3) – enigmatic – The Yellow Log (1912) – or even cartoonishly nefarious – Murder on the Road (1919). In each, the absences of colour, the well-deployed paucity of detail and the incompleteness of the brushwork belie the fully realised narratives, the immersive environments, the ironic commentary.

Edvard Munch

The Sun 1910–13

Oil on canvas

162 x 205

Munch Museum

© Munch Museum/Munch-EllingsendGroup/DACS 2012

A side room is dedicated to works reflecting on Munch’s 1930 haemorrhage in his right eye. Here scenes of a stagey externality no longer present as comprehendible, yet untranslatable, symbols of internal tableaux. Rather, the thin retinal film separating the two realities is fatally breached, and a schizophrenic co-existence permeates the work. The psychic menace of the bird emerging with primal crayon urgency in The Artist’s Injured Eye (and a Figure of a Bird’s Head) (1930) approaches the injury with neither literal representation nor metaphorical psychologising but instead with a wild, detached metonymy that reeks of wound and illness.

The closing self-portraits from the 1940s seem to embody a post-traumatic vacuity. The whiteness of the snow in Self-Portrait by the Window (1940-43) or the patchy lacunae of Self-Portrait (1940-43), combined with Munch’s averted gaze in the former and muddied blank eyes in the latter, suggests the earlier passion of existential confusion have settled into a morbid distraction. The figure of the artist is vanishing, be it formally through the empty furrows of gouache in Self-Portrait: A Quarter Past Two in the Morning (1940-44) or symbolically, uncharacteristically stepped back from the foreground and coffined between a blurred clock face and a red and black bed speaking of the flames of hell and the bars of a prison, in Self-Portrait: Between the Clock and the Bed (1940-43). Rather than the rapacious nineteenth century scourge of humanity seen in The Sick Child, the final image of death is of an understated spiritual erosion set against a fabric world of hardier materialism. And what could be more twentieth century than that?

Edvard Munch: The Modern Eye

Tate Modern, 28 June - 14 October 2012