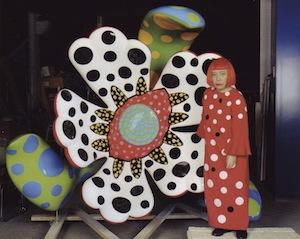

Popularly, when people think of Kusama, they think of polka dots and phalli. Both were in evidence at this comprehensive retrospective exhibition at Tate Modern. However, their infectious superabundance was kept in check by the strict chronology and even-handedness of the show, charting Kusama’s progression from precocious rejection of the Nihonga tradition in post-Hiroshima Japan through her Warholian revels in 1960s New York and back to her homeland – and a second exile – and self-admission to a psychiatric hospital in the 1970s.

Despite the range of materials and modes – oil, pen, watercolour, gouache, collage, photography, video, sculpture, miniatures, installations, triptychs that span whole walls – Kusama is consistent in her themes, her concerns and her visual rhetoric. Hers are a series of dichotomous arguments: intricacy versus expansiveness; interiority versus exteriority; the metaphysical void versus blunt physicality; singularity versus repetition.

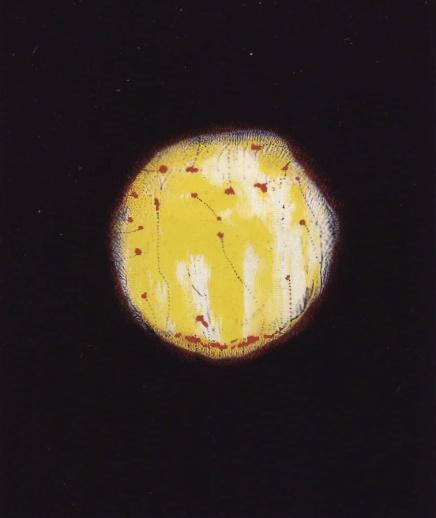

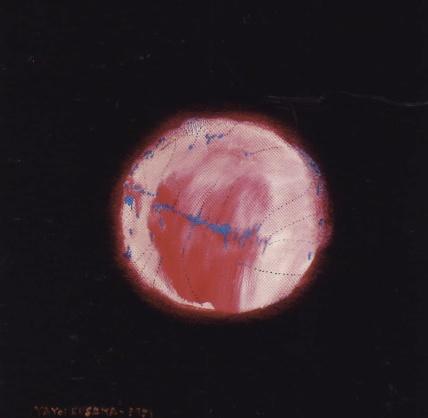

These tensions are most engagingly played out in Kusama’s elegantly reserved works on paper from the mid-1950s, many exhibited for the first time outside Japan. Here is a world of eggs and spermatozoa, of intersecting and dissecting lines, of boundaries traversed as soon as established. The counterpointing of the raging radiant energy of the nucleoid cell – one of those later, myriad polka dots caught under a scrutinising microscopic gaze perhaps – against inarguable encompassing blackness in Island No. 7 (1953) or Dots on the Sun (1953) captures the existential horror of the blinking, singular subject smothered in the eternal, and does so with a potent starkness missing from Kusama’s attention-grabbing Infinity Net series which announced her arrival on the New York art scene later that decade.

Island No.7

Dots on the Sun

Similarly, the submarine rustlings of Inward Vision No.1 (1953) and No. 4 (1953) present an obliteration through concentration and containment. These works have a suffocating intensity quite absent from the numbing dilution seen in her film Kusama’s Self-Obliteration (1967). Kusama’s 1960s accumulation sculptures, in which phalli erupt from bookcases, ladders, armchairs, boats and shoes, eradicating any empty space with the leaden tenacity of fungal spores, are often held to be witty commentaries on the sexual and consumerist excesses of the age. If this is wit, it is the wit of childish exaggeration, and it is a wit that swiftly self-consumes: Kusama’s accumulation sculptures proliferated with the same wild cancerous growth they critiqued. Much of the well-known 1960s work – bound up with Boho ‘happenings’ and hippie politics – feels very much ‘of its time’ – to be polite – or dated to the point of irrelevance – to be less so. The assortment of Kusama ephemera from the period is an unsurprising mish-mash of childishly scrawled flyer invitations to ‘friendly people’, adverts for official Kusama merchandise and her own-brand pornography, and it perhaps provides a wittier critique of the decade than a kettle stuffed with phalli. The crassness of an artistic-political mission that sold nude images and organised nudist protests, and thereby generated the very sexualised superabundance ironised by its central works, was not missed by Kusama. She soon fled America.

Kusama’s most recent output seems to have found a compromise between the moody meditations of her earlier work and the spectacle and jouissance of her 1960s heyday. Spiralling and beguiling patterns and repetitions are played out across grandly expansive, but ultimately contained, canvasses or spaces. The writhing fertility of Sprouting (The Transmigration of the Soul) (1987) or the plump fecundity of Pumpkin (1994) demonstrate a wit equally at ease with profundity and profanity.

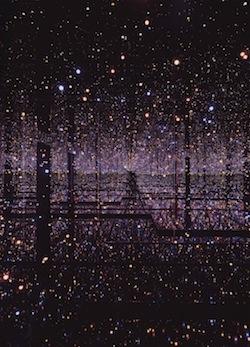

The exhibition ends with Kusama’s largest installation, the self-shattering Infinity Mirrored Room – Filled with the Brilliance of Light (2011). Differently coloured lights stretch out in all directions, simultaneously filling and emptying the spectator, who is both cosmic epicentre and lost, undifferentiated dot in the sequence of eternity. It’s a masterful expression of the duality of being a self-conscious subject within an infinite universe, and a crowning statement to an eclectic but doggedly strategic body of work.

Review by Michael J Flexer

PhD candidate, Leeds University Centre for Medical Humanities www.lcmh.wordpress.com

Writer - Apikoros Theatre Company www.apikoros.co.uk